Beyond hype — the reality of a Machine Learning project

Machine Learning (ML) is one of the fundamental components of data science. Many data problems can be framed as ML problems.

If you have studied ML, you are familiar with some of its most famous success stories, such as churn prediction, fault detection, fraud detection, search engines and recommendation systems; you may not yet be aware of everything that goes behind making an ML project successful.

In this article I will lift the veil on some of the crucial ingredients of making machine learning as effective as it can be.

A process model for ML projects

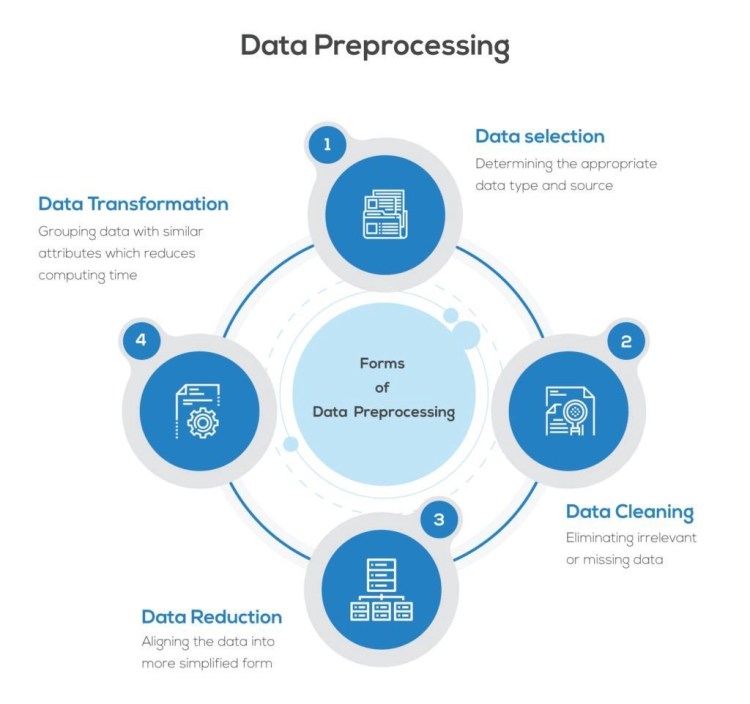

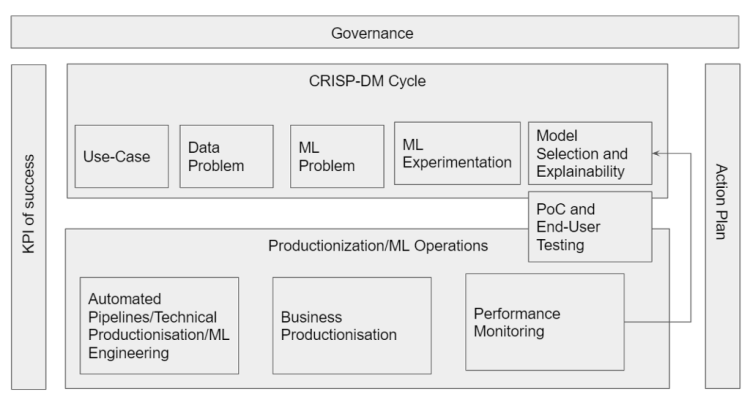

Learning the technology typically starts with the basic building blocks: how to convert a business problem into data that can be processed by an ML algorithm; how to train the algorithm (with tools such as automl); how to fill the role of an Analytics Translator (AT), whose main focus is — tech to business operationalization. Those steps, while essential, are only part of a much larger ML lifecycle model. The model is pictured below, and every ML user should be aware of it.

All steps of the process must be managed by a centralized governance department, directly under a Chief Analytics Officer or Chief Data Officer. The governance team typically consists of product owners and managers, data security experts, privacy experts, compliance experts and regulatory members.

Key steps in making an ML project succeed

Here are the team roles and essential details of each step appearing in the figure.

Use case: This is one of the most critical steps in the entire ML lifecycle. Its purpose is to ask fundamental questions before you dive into the technical tasks of data and ML (and to decide whether to do so!). Such questions include:

- What is the problem we are trying to solve?

- Is it really a ML problem, or will analytics or classical statistics be more effective?

- If we get the model, how will it be used?

- What are our KPIs of success? (Better define them ahead of time than worry about the success indicators after the application has been written, they can be updated during the experimentation phase).

- Who are the end-users and how will they interact with the application?

Trending AI Articles:

2. How AI Will Power the Next Wave of Healthcare Innovation?

Roles required at this step: analytics translator, data scientist (can serve as translator), product owner, governance team.

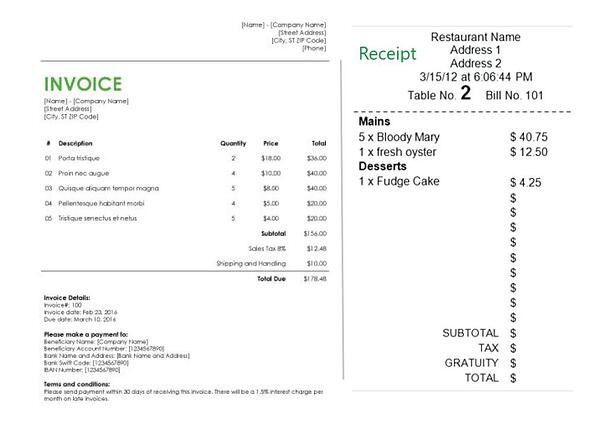

Data problem: This step maps business onto data by asking the following questions:

- What are the inputs and outputs? Where is the data stored?

- How much data do we need? Do we have enough labelled data? Do we need to collect data?

- What can we assume about the quality of the data?

- How will data be fed into such a system (batch vs stream, online vs offline, on demand vs forecast, static vs dynamic)?

ML problem: If the steps above are well defined, this part is rather easy to work out. Most ML problems fall into one of two categories: supervised (regression or classification) and unsupervised learning. For an ML practitioner, it helps to know about new ML approaches such as semi-supervised learning and active learning. An ML practitioner needs to know how ML algorithms work. Specific questions to ask are:

- What kind of ML problem do we have?

- How do we define KPIs of success at every step in the process (including: data quality, ML metrics, business metrics, prediction scores, error margins)?

- Is explainable ML needed?

- How will the output flow to the end-user?

- Do we care about the kind of algorithm we use?

- What tools will we use?

While most ML practitioners are data scientists, most ML problems only require knowledge of applied machine learning. The general set of skills needed at this step include coding ability, experience with statistics, understanding of different ML models, knowledge of experimentation frameworks such as mlops, experience with cloud computing, and experience with automl.

Roles required at this step: Applied Machine Learning practitioner, data scientist, Web/mobile app developer, and preferably a statistician.

ML experimentation: This is a classical experimentation step involving data exploration, cleaning, feature engineering, model development and experiment tracking (AutoML platforms lik modulos [2] help here). A 80–20 rule applies here: 80% cleaning plus feature engineering, 20% model building.

Model Selection, Explainability and Bias: Most parts of model development and selection can be automated using standard Python libraries (including again automl). Open-source libraries are already available to help explainability and bias analysis, and new ones are appearing all the time. Cloud providers are trying to take the lead in the race to automate the full process.

Proof of ConceptContext and End-User Testing: Before going into production, you will often create a Proof of Concept, which can consist of testing the integration of model output into the system, or just of building a simple web application around the model so that end-users can run the results and provide feedback. In a fully functional and productionized user app, one needs to bring in UX/UI designers as well. For this step you will need to have A/B and A/A testing skills available.

“Pioneer” AI organizations [1] with well-established data processes have put in place frameworks and documented instructions for most of the above steps. Though cloud service providers try to provide standardized pipelines to attract companies at this stage, most organizations are using some form of hybrid-cloud model and need access to 3rd party platforms like omega|ml [3].

ML Operations: A machine-learning project is not just a technical IT endeavor. Particularly when it reaches the deployment and operation step, it also involves business aspects. The complexity of ML operations depends upon such factors as: how often should the ML model be trained? How will the ML model be used in the end-product? How many end-users will the product handle?

Roles required at this step: data engineers, data scientists, business analysts, analytics translators, ML engineers, data product owners, end users.

Model engineering: This step requires good engineering knowledge and exposure to technological stacks that include CI/CD pipelines, DataOps, MLOps, Data Engineering and data Containerization engines.. In this vibrant area, where new ways to automate the process continue to appear regularly, you will again require a mix of engineering and business skills. The most successful AI organizations organize all projects around a well-defined ML engineering pipeline.

Business productization: This step is devoted to making sure the machine-learning solution is closely integrated with the business aspects. As a result, it too requires a mix of business and engineering skills and some user testing. It should involve people with expertise from both sides of the aisle, in particular the business professionals who will be using the output of ML algorithms.

Performance monitoring: The purpose of this step, which is also called post-production monitoring, is to assess how the ML solution actually works. It involves tracking the evolution of a number of parameters over time: modeling and business KPIs as well as data-related aspects, particularly data, concept and covariate drift. Without this step, there is a risk that an initially adequate ML system will progressively degrade because the training set no longer reflects the current data. Effective performance monitoring enables the data owner to trigger appropriate recalibration processes if this phenomenon passes a certain statistical threshold.

Governance: Any ML-based system must include, during development and after deployment, a strong governance system defining KPIs and action plans in response to possible hiccups. Governance should be under the domain of a governing body directly under the Chief Data Officer or Chief Analytics Officer.

Towards a holistic view of the ML process and its integration into the business process

In spite of all the hype around AI, many companies are still struggling to profit from AI. Why is that and what can you do about it? A core reason is the dire shortage of people who understand the full process as outlined above — taught, in full depth, in Propulsion’s courses.

We developed Propulsion’s ML course [4] by leveraging the experience of over 60 ML projects delivered over the past four years across a wide range of Swiss companies and industries. The course also relies on extensive market research to identify areas leading to ML failures in organizations.

The result is a course that integrates not only the latest and brightest ML tools and techniques, at the forefront of today’s rapidly evolving ML technology, but also numerous elements that you cannot get by studying technology alone: all the business aspects, rooted in an in-depth understanding of what makes ML succeed or fail in a company.

This is the kind of hot skill that companies badly need today. If you are interested in acquiring it to make your future employer’s ML projects be part of the success stories, we look forward to receiving your applications. If you like this article (and the others on this blog), please share it in your network!

[1]. Propulsion Academy Blog: Whom should organizations re-skill or hire to succeed in the age of AI and how to become an AI Pioneer?

[2]. modulos

[3]. omega|ml

[4]. Propulsion Academy Machine Learning course

Don’t forget to give us your ? !

Beyond hype — the reality of a Machine Learning project was originally published in Becoming Human: Artificial Intelligence Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.