The story of machine proofs — Part II

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Landscape part-1 (Theorem prover as a system)

- Accomplishments

- Theorem Proving Systems — Tradeoffs & Architectures

- Landscape part-2 (Distribution of efforts across provers)

- Conclusion

Introduction

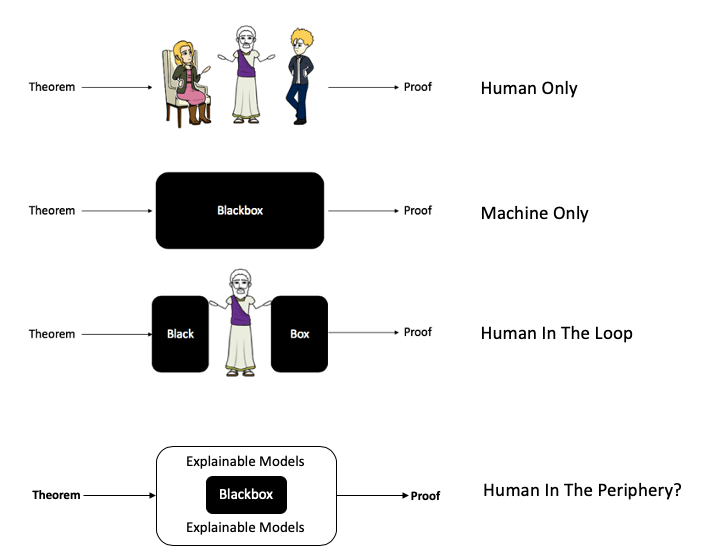

A quick recap. In “The story of machine proofs — Part-1”, we covered how humans approached formal mathematical proofs, then introduced early attempts at machine proofs and ended with this picture depicting our journey to Centaur Theorem Provers. (Figure-1):

We’ll dig into both the machine-only and human-in-the-loop provers but here’s what you can expect to take away from part-2 of this series:

- Landscape of theorem provers;

- Comparison: Where they differ from one another;

- Status check: How close machines have gotten to humans in the automated reasoning race

One point to note is that humans have been in the loop for a while now so it is more the degree of their involvement that has changed over the years. As noted back in 1969 in Semi-Automated Mathematics [Guard et al.], the idea isn’t new.

“Semi-automated mathematics is an approach to theorem-proving which seeks to combine automatic logic routines with ordinary proof procedures in such a manner that the resulting procedure is both efficient and subject to human intervention in the form of control and guidance. Because it makes the mathematician an essential factor in the quest to establish theorems, this approach is a departure from the usual theorem-proving attempts in which the computer unaided seeks to establish proofs.”

But it has required deliberate attention and effort to generate human readable proofs or any intermediate meaningful representations at critical stages of the pipeline in order to allow humans to guide the machine and co-create proofs.

Trending AI Articles:

Let’s start with some wins from computer assisted proofs in the last few decades:

- [1976] Four color theorem

- [1982] Mitchell Feigenbaum’s universality conjecture in non-linear dynamics

- [1988] Connect Four

- [1989] Non-existence of a finite projective plane of order 10

- [1996] Robbins conjecture

- [1998] Kepler conjecture, the problem of optimal sphere packing in a box

- [2002] Lorenz attractor, –14th of Smale’s problems

- [2006] 17-point case of the Happy Ending problem

- [2008] NP-hardness of minimum-weight triangulation

- [2010] Optimal solutions for Rubik’s Cube can be obtained in at most 20 face moves

- [2012] Minimum number of clues for a solvable Sudoku puzzle is 17

- [2014] A special case of the Erdős discrepancy problem was solved using a SAT-solver.

- [2016] Boolean Pythagorean triples problem

- [2019] Kazhdan’s property (T) for the automorphism group of a free groupof rank at least five

A note on SAT-solver mentioned above – It is a very important concept in the context of theorem provers. SAT stands for SATisfiability. The idea is that if we can replace variables in a boolean expression or formula by TRUE or FALSE such that the formula evaluates to TRUE, then we consider it to be satisfiable. This turns out to be an NP-complete problem, that is, there is currently NO known algorithm (yet to be “proven” though — see P vs NP) that can solve all possible input instances in polynomial time. That said, A SAT-solver uses efficient heuristic approaches and approximations and is heavily used to solve problems in the semiconductor space, AI and Automated Theorem Proving. Just within EDA (Electronic Design Automation) where I spent over 15 years I’ve seen it be actively used for combinational equivalence checking, logic optimizations, circuit delay computation, bounded model checking and test pattern generation.

Back to theorem provers …

Landscape part-1

“Names don’t constitute knowledge!”

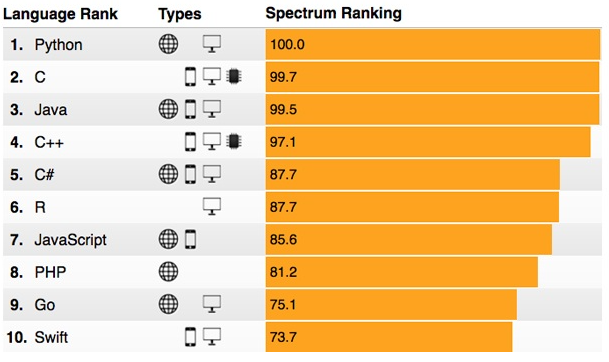

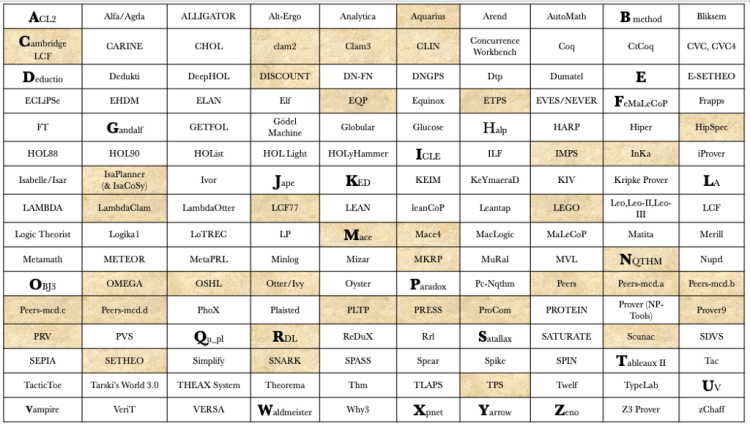

To get at the landscape, I boiled the ocean a bit and compiled several efforts around automated reasoning from theorem provers and verifiers to related tools and languages risking some redundancy and scope creep. But at this point I’d rather it be an overkill than a best-of list so that we get to see the field in its entirety. Here’s a flat list (Figure-2) organized alphabetically with most if not all efforts in the last few decades.

Really? A perfect 10 x 16 table with 160 cells? I either got lucky or just kept finding new ones until there was diminishing returns. (the latter!)

Feynman would have taken one look at that table and said what do you want me to do with 160 names? “Names don’t constitute knowledge!”. Here’s a short “blast” from the past that is very well worth the watch:

Even if I say those names are indices into strategies and tactics for theorem proving such as graph based resolution, induction, model generation, proof planning, semi-automatic interactive interfaces, programmability, intuitionistic predicate logic, multi-valued logic, constraint solvers etc. I wouldn’t be adding much value as they’re still just names, perhaps a tad bit more descriptive.

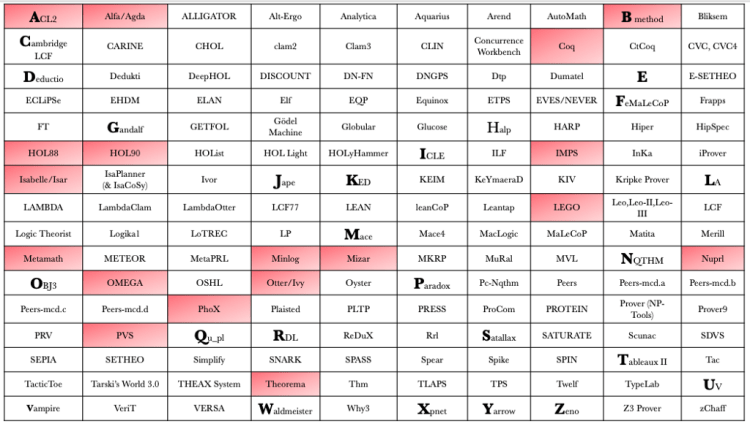

So how then do we slice and dice the above list? Maybe by categories of logical systems and reasoning engines (resolution, interactive, induction, satisfiability checking, model checking, constraint solvers…)? Or something like what the “theorem prover museum” (yes, museum!) does? Their goal is to archive all systems with source code and metadata. They compiled 30 odd theorem provers dating back to 1955 (Logic Theorist) and 1960 (OTTER). The highlighted cells in Figure-3 below are ones from the museum.

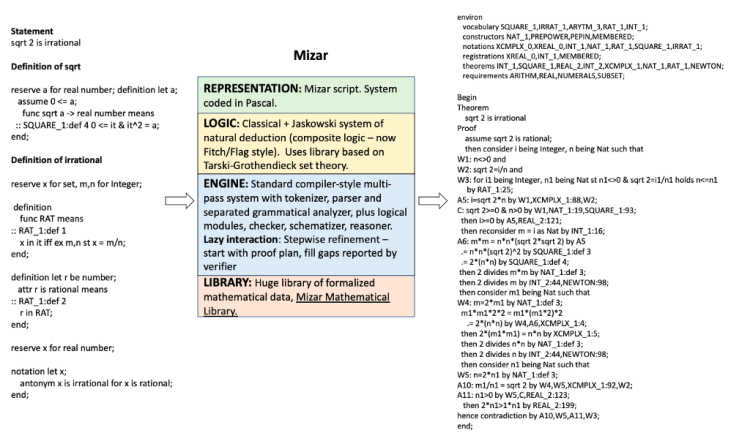

But another compilation, a more interesting one is Freek Wiedijk’s “The Seventeen Provers of the World” in which he asked authors working on the top active (at the time — 2005) theorem provers to provide their machine proof for the same one problem — irrationality of sqrt(2).

While I had explored different approaches to the Pythagoraean theorem across time in part-1 going back all the way to the Babylonian tablet (Plimpton 322), what I really like about Freek’s approach is the structure and template with targeted questions that he provided to the authors making it easier to compare different approaches to the same problem. We will spend a considerable portion of part-2 discussing his paper. If you’re curious which theorem provers he picked (or got responses for), see Figure-4 below. Only 4 of his 17 appear in the museum above — IMPS, LEGO, Omega and OTTER.

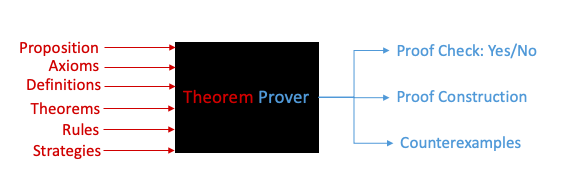

Theorem Prover — A system

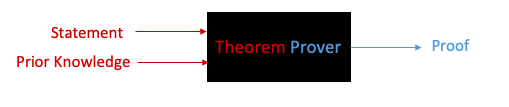

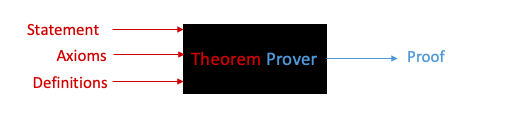

Before we get into why or how theorem provers differ from one another, let us frame the prover as a system with input, output and a process. Figure-5 shows a blackbox that is fed with a theorem. And the output is a proof.

Let us expand further on the system notion with a concrete example:

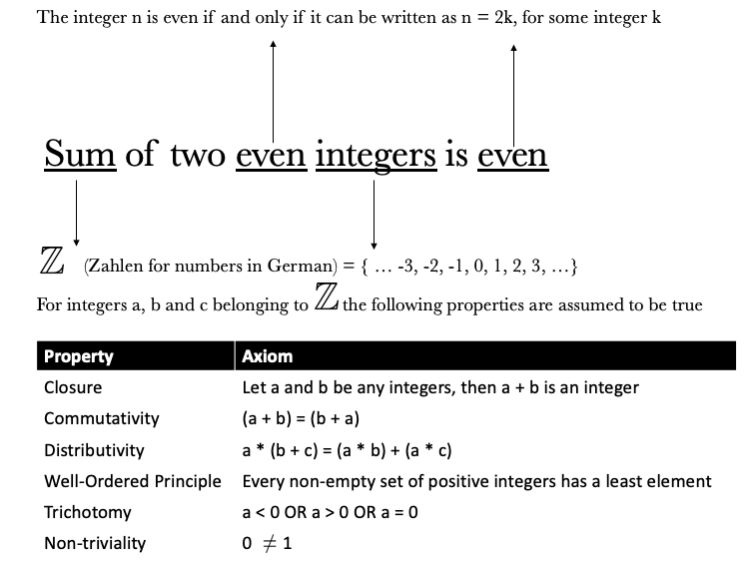

Theorem: “The sum of two even integers is even”.

So the above theorem is our input. Wait! The words theorem, lemma, proposition and corollary are sometimes used interchangeably as the differences are mildly subjective. And the word theorem is typically reserved for a strong or major result that has been proven to be true. Lemma is a relatively minor result popularly acknowledged as a helping or auxiliary theorem. Proposition is even less important but interesting still. And corollary is a consequent result that can be readily deduced from a theorem. For our purposes, let’s then go with just a plain statement as input to the engine before we elevate its status to that of a theorem (Figure–6)

Now to prove the statement “The sum of two even integers is even”, we need to first understand everything about that statement, i.e. surface all prior knowledge about the terms and concepts involved (Figure-7).

Prior knowledge in this example includes definitions and properties of integers some of which are assumed to be true i.e. axioms. Here’s what we know about integers (Figure-8)

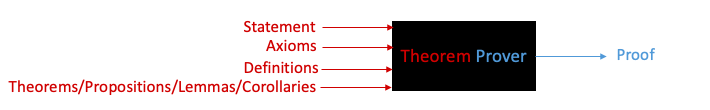

That statement was deceptively simple! The one input has grown to 3 inputs to include axioms and definitions as shown in Figure-9 and will grow to 4 (Figure-10) when we pull in previously proven theorems.

Now we need to know what to do with the knowledge, i.e. strategies and clear rules on how to use the knowledge about the statement (Figure-11)

Let us shift attention to the right hand side, i.e. the output. A proof assistant can not only provide the construction of a proof but also check the validity of a proof (Is the statement true or false) and additionally generate counterexamples. So the system can have multiple outputs as well. We call them proof checkers or verifiers.

The above Figure-12 system holds true for all theorem provers. But what exactly happens inside an automated theorem prover (ATP)? Figure-13 shows a flowchart for the ATP process from TPTP (Thousands of Problems for Theorem Provers) which begins with checking syntax and semantics, then checking the consistency and satisfiability of the axioms followed by establishing a logical consequence before proving the theorem and verifying the proof.

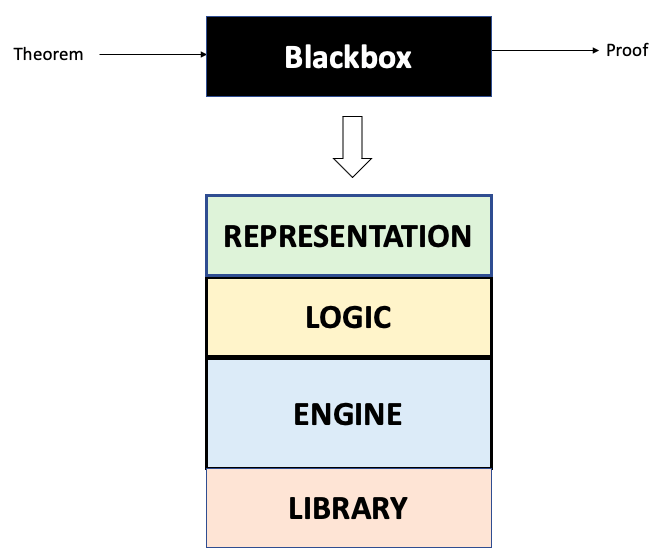

So where do all provers differ? The answer to that lies in the fundamental building blocks of AI — Representation and Reasoning.

- Representation: What formal language do we use for mapping the world to the machine; “Each formalism has its intrinsic axioms as the starting point for the prover. Nevertheless, custom axioms can help the prover advance more rapidly with the resolution process in the next step.”

- Reasoning: What algorithms do we use to manipulate the formal expressions. Additionally how the rules are generated (human experts, machine learned or hybrid) is important. “The prover has several techniques at its disposal to process the theorems and the system description. Some examples, among many others, are: Rewriting — substitute terms to simplify computations; Skolemization — elimination of existential quantifiers (∃), leaving only universal ones (∀); Tableaux — break down a theorem into its constituent parts and prove or refute them separately”.

The blackbox in our once-simple system essentially breaks down as shown in Figure-14 where reasoning is split into the logical formalism and the reasoning engine.

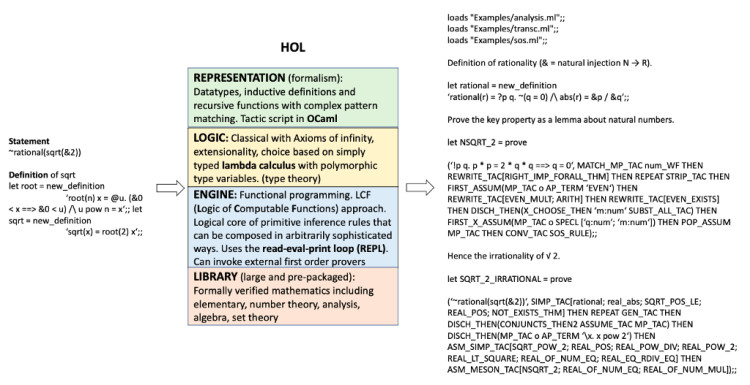

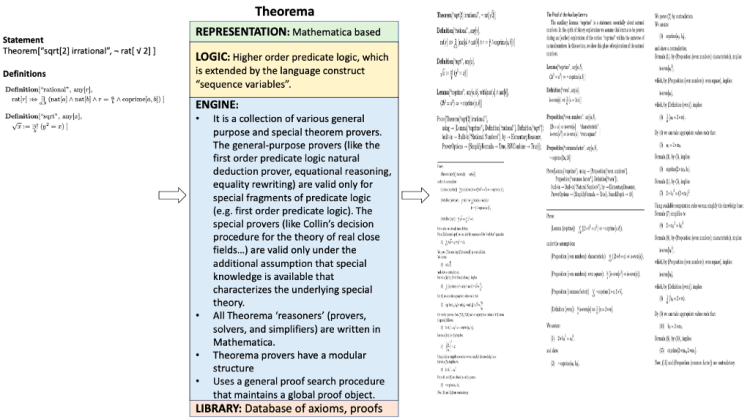

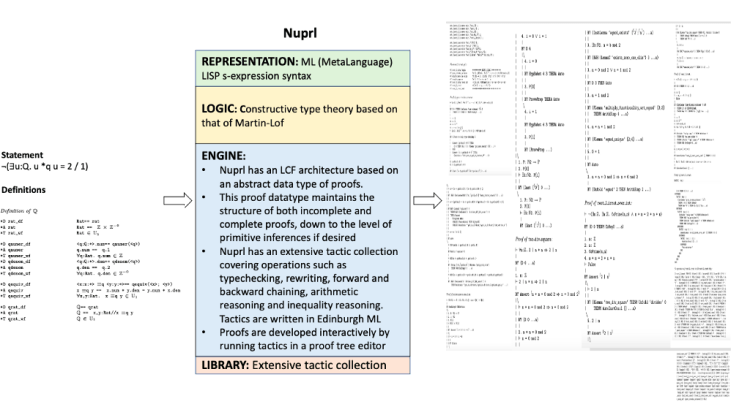

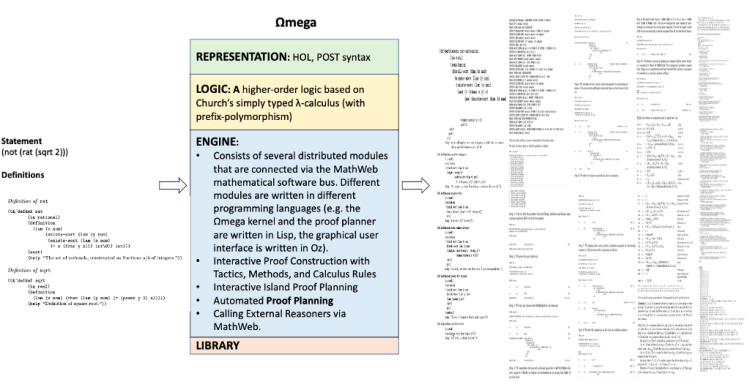

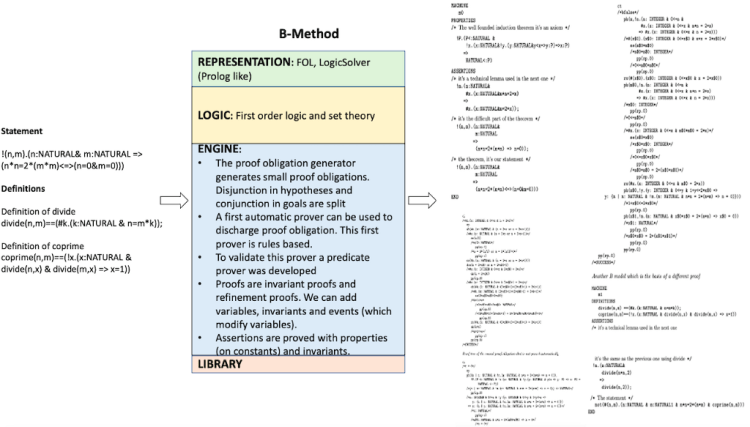

We’ll use the above template to walkthrough Freek’s seventeen theorem provers.

[Sidenote: While I have reframed the authors’ responses to Freek’s question so as to fit the above template, I would like to acknowledge that the underlying content is entirely from the paper and any error in translation/representation is solely my responsibility. I would also suggest that you refer to the paper for a richer and more detailed explanation of each solution.]

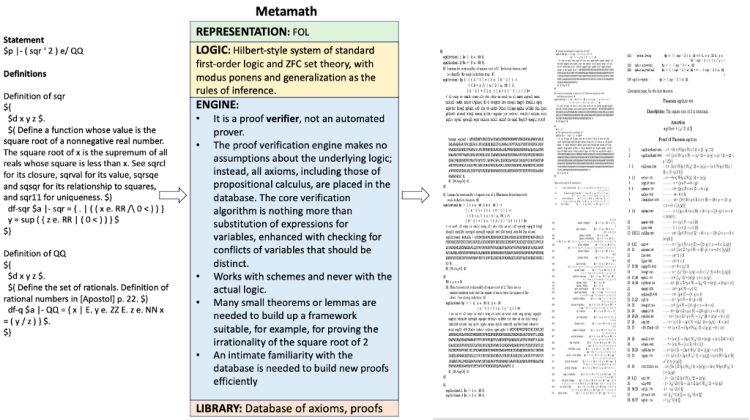

Do you have to go through all 17 provers? Not necessary. But if you’re curious, it can be interesting. My suggestion would be to skim through the notes in the centre table and just glance at the input and output to get a sense of what the machines take in and spit out. In some of the provers further down, the proofs are too long (like IMPS, Metamath, Nuprl) to even print here so they’ve been compressed to fit the template and will be hard to read anyway. I still wanted them in here to give readers a sense of the formats and readability. If after a few it seems overwhelming feel free to jump ahead to the accomplishments section.

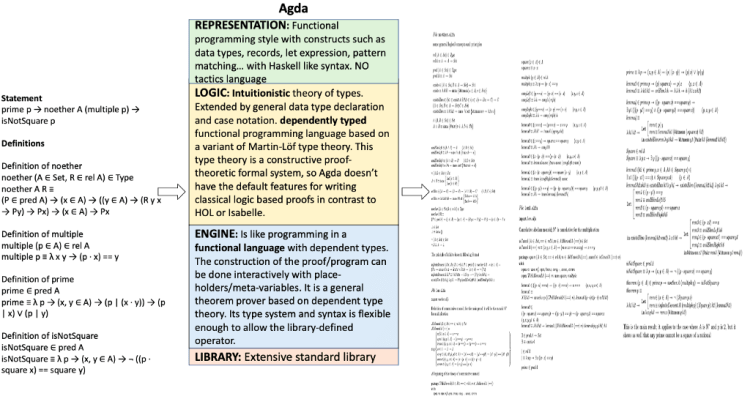

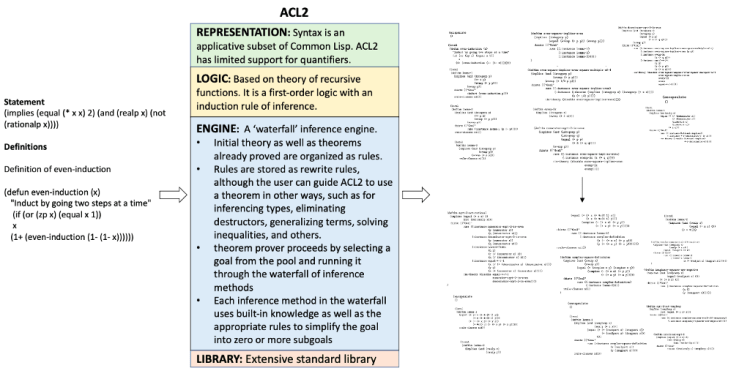

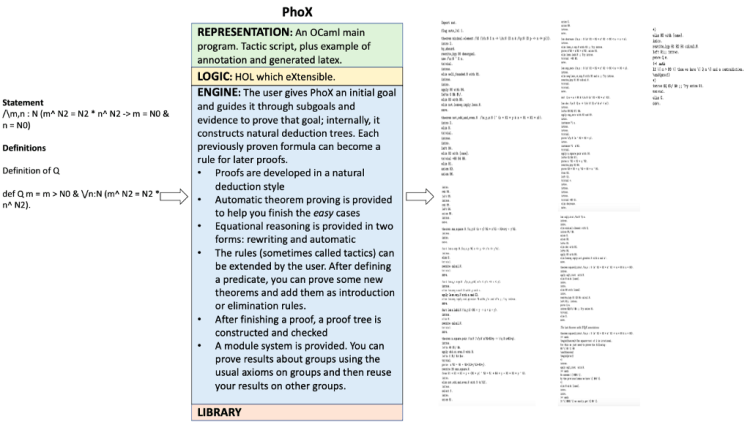

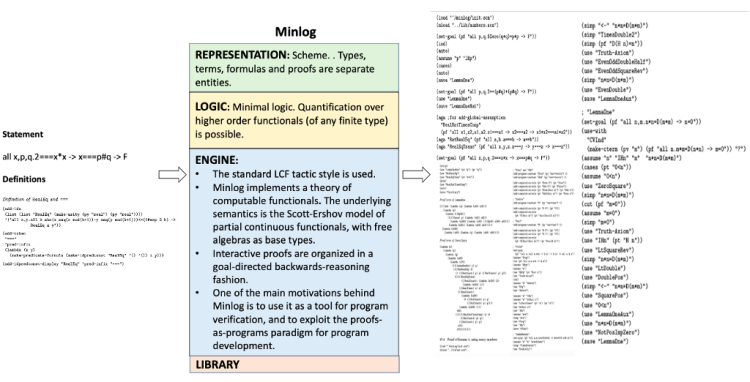

How to read the picture?

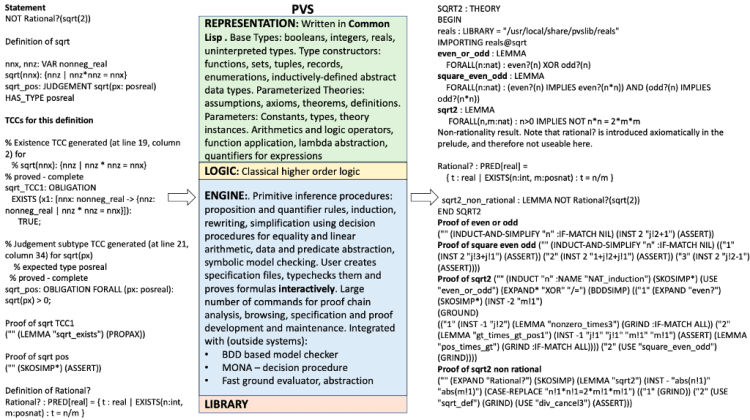

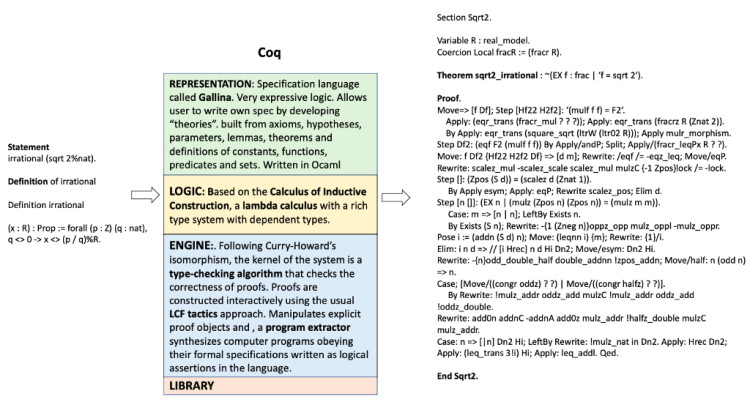

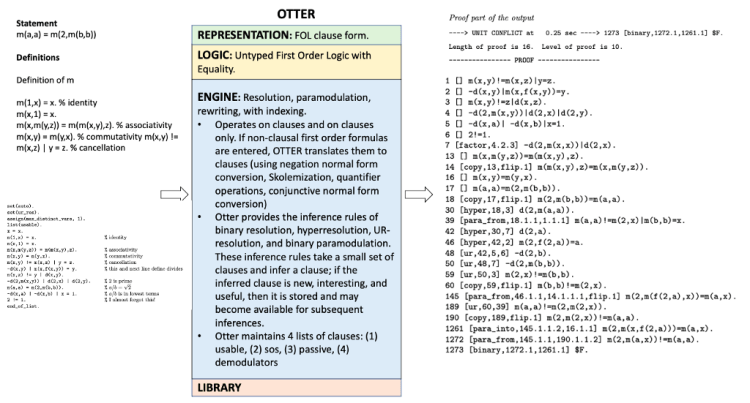

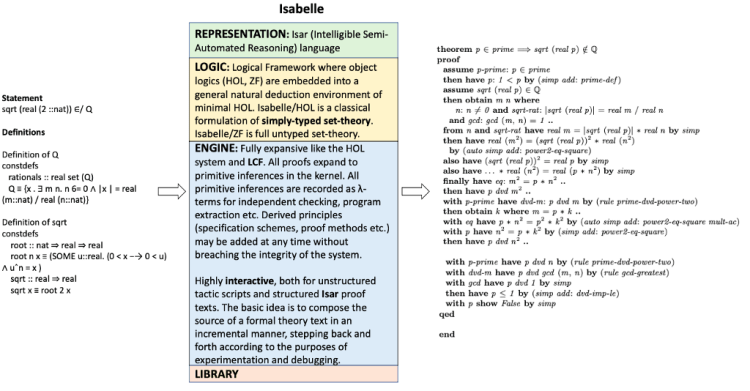

The input on the left hand side includes the statement to be proven along with relevant definitions both specified in the language (i.e. REPRESENTATION in green box). The output proof also typically uses the same language. The LOGIC (yellow box) and ENGINE (blue box) together give us the rules and approaches to operate on the input. For instance, in the PVS prover the inputs are written in common LISP using a higher order logic system. Operations such as induction, rewriting, symbolic model checking or simplification using decision procedures will be applied on the input to generate proof chains. In PVS, the user can interact by creating specification files, type checking them and providing proofs.

1. HOL: Higher Order Logic Theorem Prover

Figure-16 shows the family tree of provers going from LCF (Logic of Computable Functions) to HOL (Higher Order Logic).

2. Mizar

References:

- http://mizar.org/

- Presenting and Explaining Mizar — Josef Urban:

- Geuvers, H. Proof assistants: History, ideas and future

3. PVS = Prototype Verification System

PVS is an interactive theorem prover. The philosophy behind the PVS logic has been to exploit mechanization in order to augment the expressiveness of the logic

References:

4. Coq

References:

5. OTTER

OTTER: Organized Techniques for Theorem-Proving and Effective Research.

References:

6. Isabelle

References:

7. Alfa/Agda

References:

- Integrating an Automated Theorem Prover into Agda

- Constructive and Non-Constructive Proofs in Agda (Part 2): Agda in a Nutshell

8. ACL2

ACL2 (“A Computational Logic for Applicative Common Lisp”) is a software system consisting of a programming language, an extensible theory in a first-order logic, and an automated theorem prover.

9. PhoX

Reference:

10. IMPS

Reference:

- https://github.com/theoremprover-museum/imps

- IMPS: An Interactive Mathematical Proof System — William M. Farmer, Joshua D. Guttman, F. Javier Thayer

11. Metamath

Reference:

12. Theorema

Reference:

13. LEGO

Reference:

14. Nuprl

Reference:

15. Omega

16. B method

Reference:

- Software Component Design with the B Method — A Formalization in Isabelle/HOL — David Déharbe, Stephan Merz

17. Minlog

Reference:

- The Minlog System

- Minlog — A Tool for Program Extraction Supporting Algebras and Coalgebras — Ulrich Berger, Kenji Miyamoto, Helmut Schwichtenberg, and Monika Seisenberger

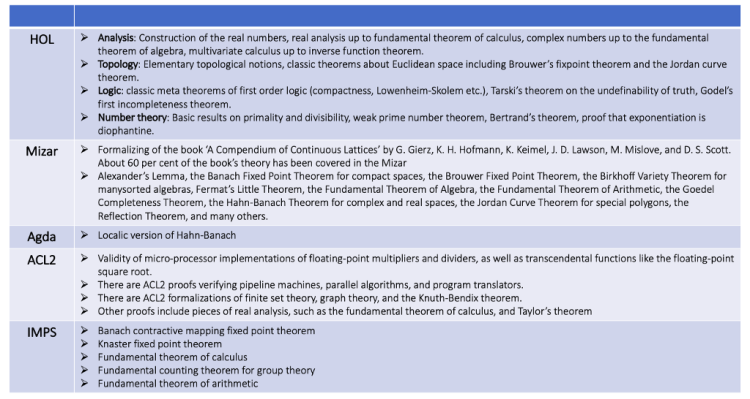

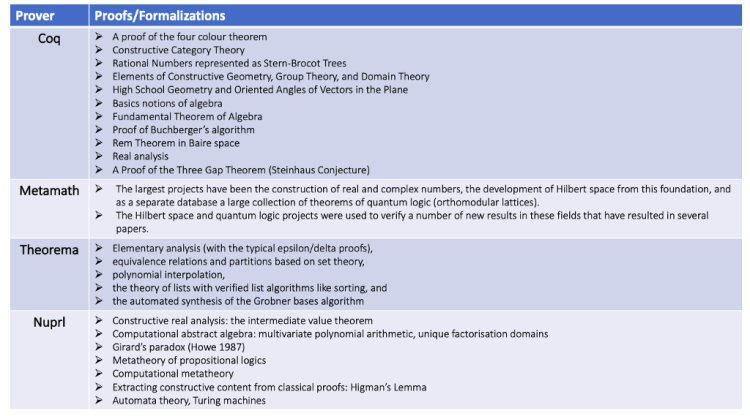

Accomplishments: Formalizations by provers

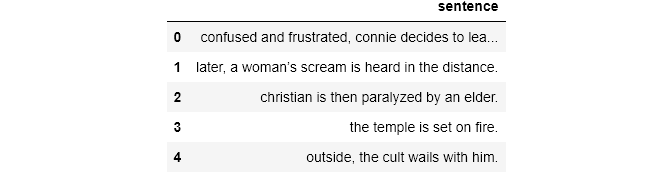

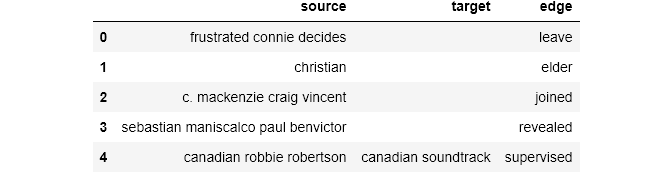

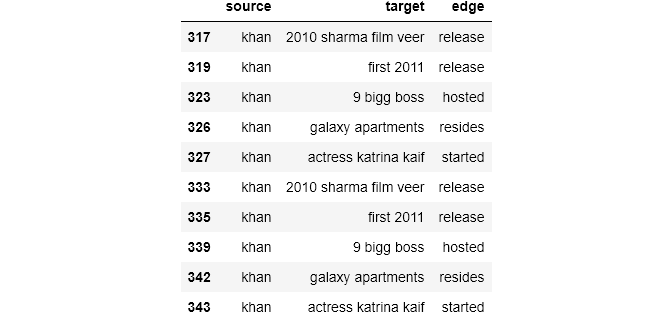

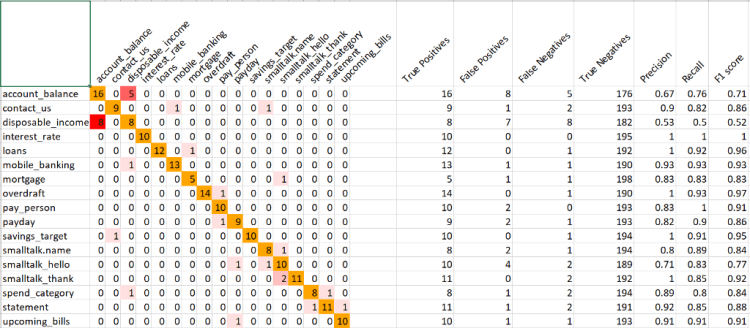

In the tables below (Figures 33–35), we can see an impressive list of formalizations from some of the above provers.

Theorem Proving Systems: Tradeoffs & Architectures

Tradeoffs

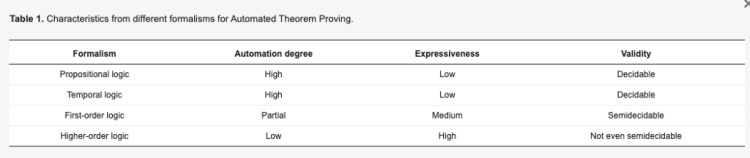

As shown in the above sections, even among just these 17 provers some use higher order logic, first order logic and ZFC set theory while others use Tarski-Grothendieck set theory which is a non-conservative extension of ZFC that includes the Tarski’s axiom to help prove more theorems. Some use Hilbert-style axiomatic systems while others use Jaskowski’s system of natural deduction where proofs are based on the use of assumptions which are freely introduced but dropped under some conditions. Some use classical logic systems while others use intuitionistic or constructive logic which is a restriction of classical logic wherein the law of excluded middle and double negation elimination have been removed. And one uses LUTINS (Logic of Undefined Terms for Inference in a Natural Styles), a variant of Church’s simple type theory

Type theory was originally introduced in contrast to set theory to avoid paradoxes and is known to be more expressive. But expressiveness tends to impact automation negatively. As noted in this article “A Survey on Formal Verification Techniques for Safety-Critical Systems-on-Chip”: (Figure-36)

“…increase in expressiveness has the inverse effect on automation. The more expressive a logic is, the less automated it can be. This means that tools for higher-order logic usually work iteratively, where the user is responsible for providing simpler proofs to help guide the verification process.”

With each choice there is a tradeoff. But to help tease these tradeoffs out in a foolproof or reliable and faster way, we need help. The turnaround time for humans to spot an error, correct it and re-check can be far too long. Around 1900, Bertrand Russell, a mathematician, logician and philosopher found a bug (Russell’s paradox) in set theory which eventually led to the discovery/invention of type theory. A hundred years later around 2000, Vladimir Voevodsky (a Fields medalist) finds an error in his own paper (written seven years earlier!) which leads to the discovery/invention of univalent foundations. Voevodsky notes in this article titled The Origins and Motivations of Univalent Foundations the following:

“In 1999–2000, again at the IAS, I was giving a series of lectures, and Pierre Deligne (Professor in the School of Mathematics) was taking notes and checking every step of my arguments. Only then did I discover that the proof of a key lemma in my paper contained a mistake and that the lemma, as stated, could not be salvaged. Fortunately, I was able to prove a weaker and more complicated lemma, which turned out to be sufficient for all applications. A corrected sequence of arguments was published in 2006. This story got me scared. Starting from 1993, multiple groups of mathematicians studied my paper at seminars and used it in their work and none of them noticed the mistake. And it clearly was not an accident. A technical argument by a trusted author, which is hard to check and looks similar to arguments known to be correct, is hardly ever checked in detail.”

Voevodsky goes on to propose a new homotypy type theory to provide univalent foundations for mathematics, based on relations between homotopy and type theory. This helped formalize a considerable amount of mathematics and proof assistants such as Coq and Agda moving the needle in ATP.

Choices such as set theory versus type theory are so core to automated reasoning that this field needs a much deeper understanding of the fundamentals of mathematics and hence needs a lot more mathematicians to work alongside computer scientists, logicians and philosophers to accelerate progress. In this very nicely written article titled Will Computers Redefine the Roots of Math?, the author talks about a recent cross disciplinary collaboration which we need more of:

Along with Thierry Coquand, a computer scientist at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, Voevodsky and Awodey organized a special research year to take place at IAS during the 2012–2013 academic year. More than thirty computer scientists, logicians and mathematicians came from around the world to participate. Voevodsky said the ideas they discussed were so strange that at the outset, “there wasn’t a single person there who was entirely comfortable with it.” The ideas may have been slightly alien, but they were also exciting. Shulman deferred the start of a new job in order to take part in the project. “I think a lot of us felt we were on the cusp of something big, something really important,” he said, “and it was worth making some sacrifices to be involved with the genesis of it.”

Architectures

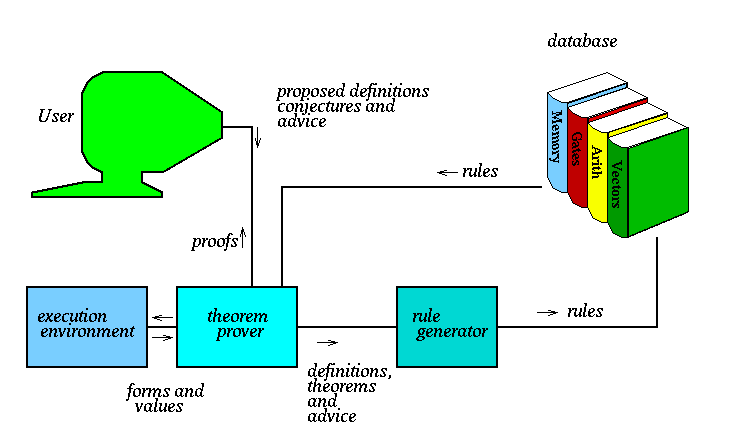

One trend to note is that the complexity of theorem provers has slowly been growing from simple systems to system of systems, i.e. pulling in the best reasoners from multiple sources. But this also means that maintaining such systems (for performance, robustness, accuracy, reliability) is getting harder. Let’s take a sneak peak at the architectures of some of them: ACL2, Omega, LEAN, ALLIGATOR, iGeoTutor/GeoLogic, Matryoshka and Keymaera.

ACL2

We saw ACL2 earlier. It has an IDE supporting several modes of interaction, it provides a powerful termination analysis engine and has automatic bug-finding methods. Most notably, ACL2 (and its precursor Nqthm) won the ACM Software System Award in 2005 (Boyer-Moore Theorem Prover) which is awarded to software systems that have had a lasting influence. Figure-37 shows a high-level flow.

Omega

We saw Omega earlier as well. Interesting to note here (Figure-38) is how external reasoners (like OTTER, SPASS for first-order or TPS, LEO for higher order) are invoked as needed.

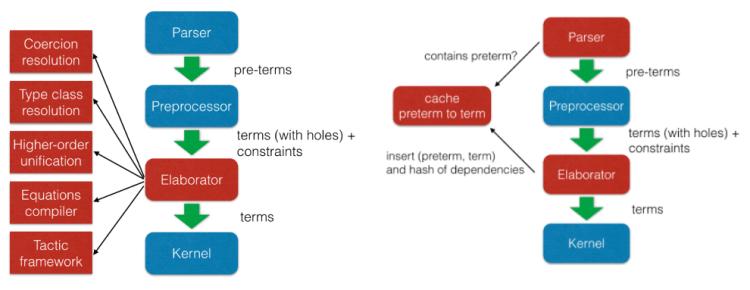

LEAN

LEAN is an open source theorem prover developed at Microsoft Research and CMU. It is based on the logical foundations of CiC (Calculus of Inductive Constructions) and has a small trusted kernel. It brings together tools and approaches into a common framework to allow for user interaction hence bringing ATP and ITP closer. Figure-39 shows some of the key modules.

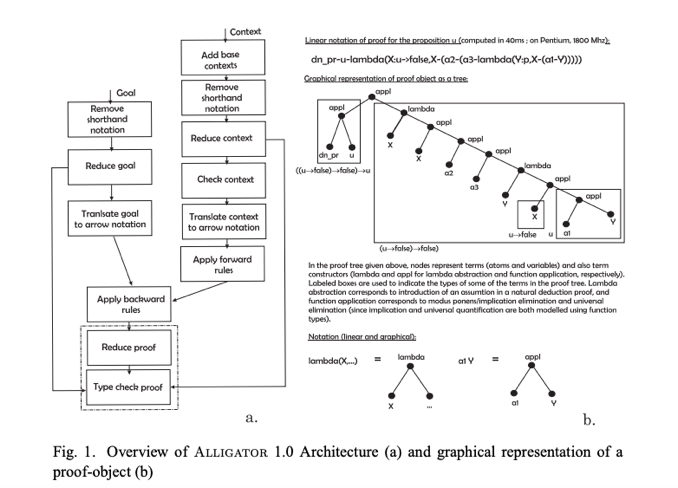

ALLGATOR

ALLIGATOR is a natural deduction theorem prover based on dependent type systems. It breaks goals down and generates proof objects (text files with assertions leading to a conclusion), an interesting part of the architecture shown in Figure-40. As noted in the paper “The ALLIGATOR Theorem Prover for Dependent Type Systems: Description and Proof Sample”, the authors identify the following key advantages of having proof objects:

- Reliability: Satisfies de Bruijn’s criterion that an algorithm can check the proof objects easily.

- Naturalness: Based on natural deduction (closer to human reasoning — less axiomatic)

- Relevance: Proof objects can identify proofs which are valid but spurious (do not consume their premises)

- Justification of behavior: Proof objects provide direct access to the justifications that an agent has for the conclusions and the interpretations that it constructs, i.e. more explainability.

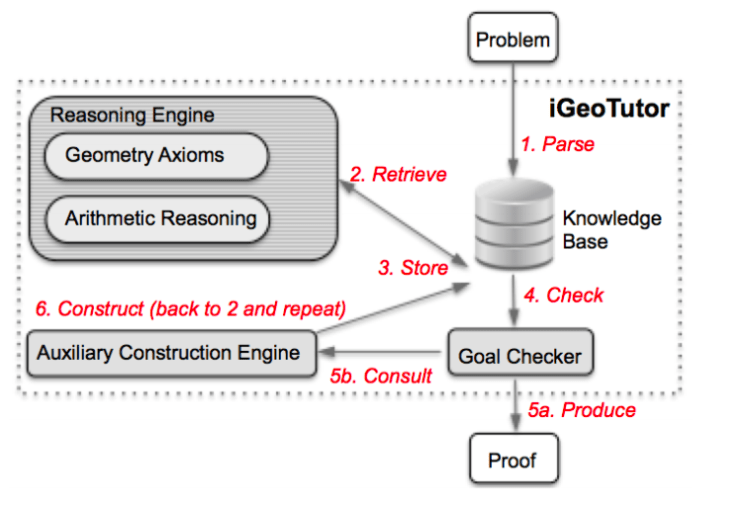

iGeoTutor and GeoLogic

An important goal in efforts like iGeoTutor (See Automated Geometry Theorem Proving for Human-Readable Proofs, Figure-41) and GeoLogic is to generate more human readable proofs in geometry. GeoLogic is a logic system for Euclidean geometry allowing users to interact with the logic system and visualize the geometry (equal distances, point being on a line …). Here’s a detailed presentation by Pedro Quaresma on Geometric Automated Theorem Proving dating back to efforts in 1959 by H.Gelerntner (See Realization of a geometry-theorem proving machine)

Matryoshka

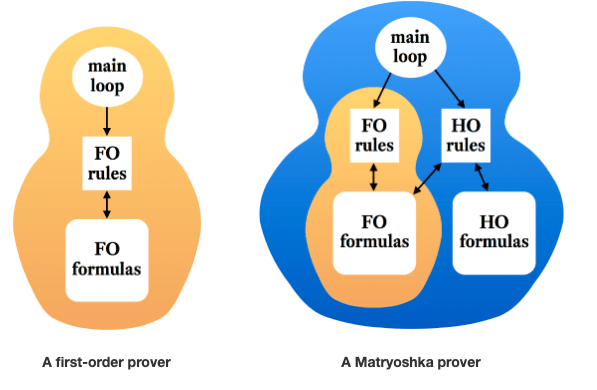

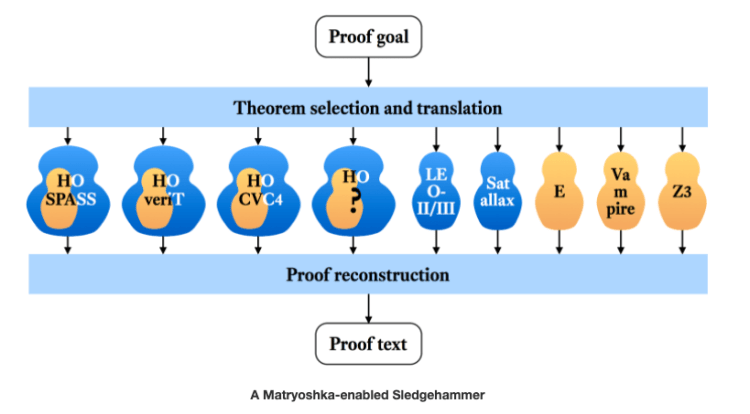

Matryoshka fuses two lines of research — Automated Theorem Proving and Interactive Theorem Proving. These systems are based on the premise that first-order (FO) provers are best suited for performing most of the logical work but they go on to to enrich superposition (Resolution+Rewriting) and SMT (Satisfiability Module Theories) with higher-order (HO) reasoning to preserve their desirable properties (Figure-42 and Figure-43)

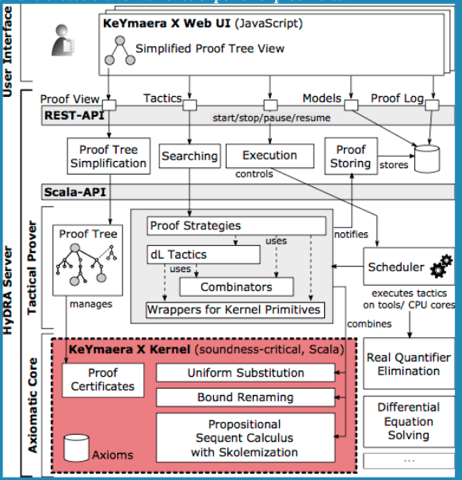

KeYmaera

KeYmaera is a theorem prover for differential dynamic logic for verifying properties of hybrid systems (i.e. mixed discrete and continuous dynamics). Figure-44 shows three big parts to the system — the axiomatic core, the tactical prover and the user interface. The architecture gives us a sense of the multiple moving parts.

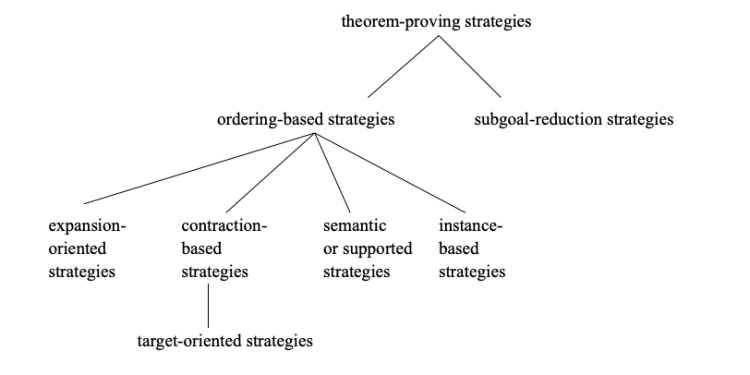

What I do find missing though is a single picture describing the entire design space of theorem provers that captures key dimensions and situates automated and interactive theorem provers, Lean based provers, resolution and Tableau provers, SMT and SAT provers, model checkers, equational reasoning, quantifier-free combination of first order theories, conflict-driven theory combination and the more recent machine learning based ones. Maybe it exists but neither could I find one easily and nor am I currently qualified (as an ATP enthusiast) enough to weave one together (perhaps a future project). I did like this taxonomy from back in 1999 in the paper “A taxonomy of theorem-proving strategies” but it is dated and limited to first-order theorem proving (Figure-45).

Landscape (part 2) — Distribution of efforts

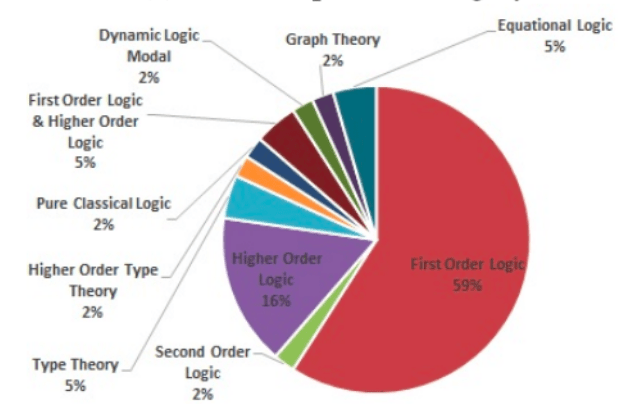

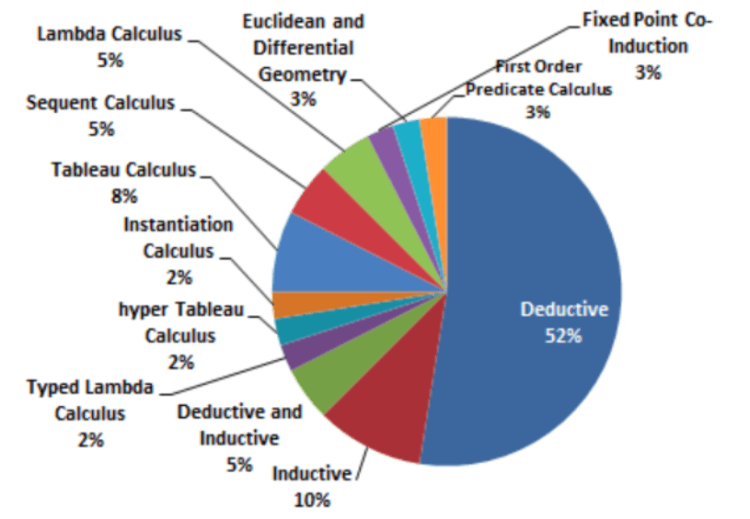

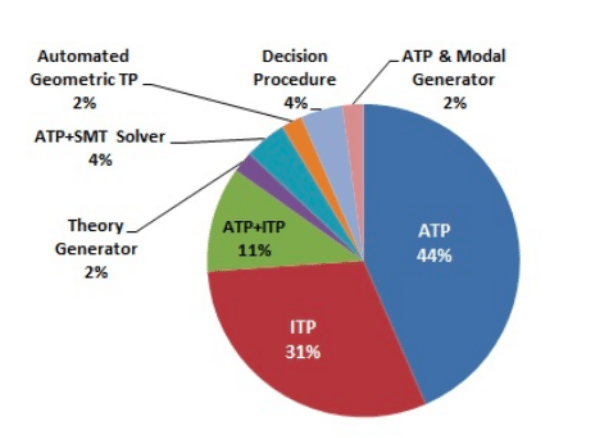

One of the surveys on theorem provers showed a significant percentage of efforts are first order logic provers (Figure-46) and the most popular calculus of reasoning is deduction. (Figure-47)

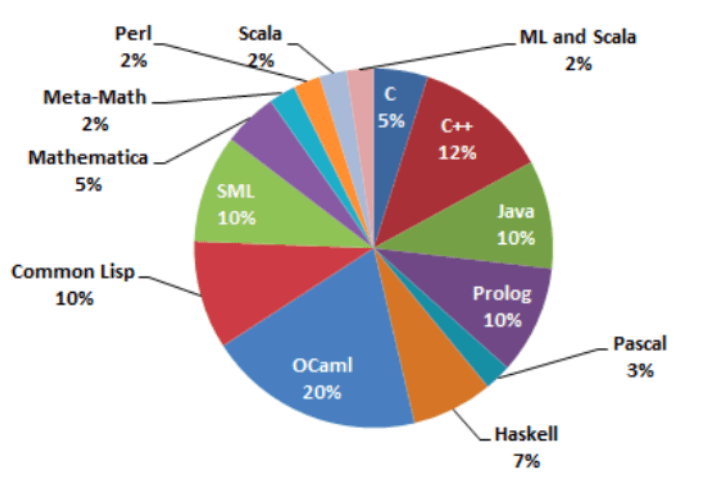

Look at the variety of languages used across provers. They range from ML (MetaLanguage) and its dialects like OCaml (Objective Categorical Abstract Machine Language), Prolog, Pascal, Mathematica, Lisp and its dialect Scheme to more esoteric specification languages like Gallina (exclusively for Coq). Other theorem provers not mentioned here use Scala, C/C++, Java, SML or Haskell. As for the reasoning engines, some use functional programming, some have a proof plan with goals that are automatically broken down into sub-goals, some are interactive while others pull in multiple external reasoning systems or model checkers.

The same survey above also broke down the programming designs (Figure-48) and languages (Figure-49) across provers indicating that close to a quarter of the efforts use functional programming with OCaml as the choice of language.

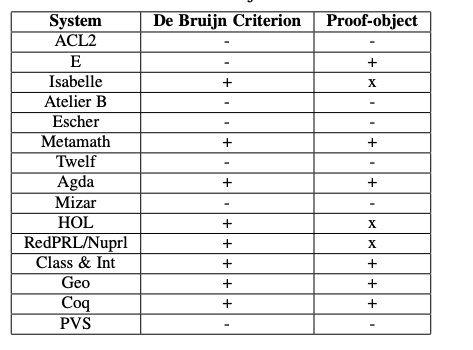

In addition to the above differences, as noted in “A Survey on Theorem Provers in Formal Methods”, there are some criteria like de Bruijn’s criterion and Poincare’s principle to help determine how good a prover is. According to the de Bruijn criterion “the correctness of the mathematics in the system should be guaranteed by a small checker”. That is generate proofs that can be certified by a simple, separate checker known as the ‘proof kernel’. So if a prover has a small proof kernel, then it improves the reliability. Figure-50 shows which provers satisfy the criterion and which don’t.

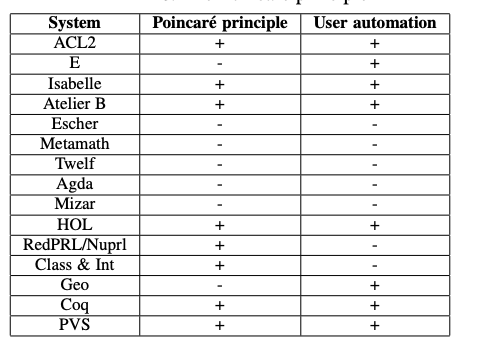

And a theorem prover satisfies the Poincare principle, if it has the ability to automatically prove the correctness of calculations or smaller trivial tasks. Figure-51 shows which provers satisfy the principle and which don’t.

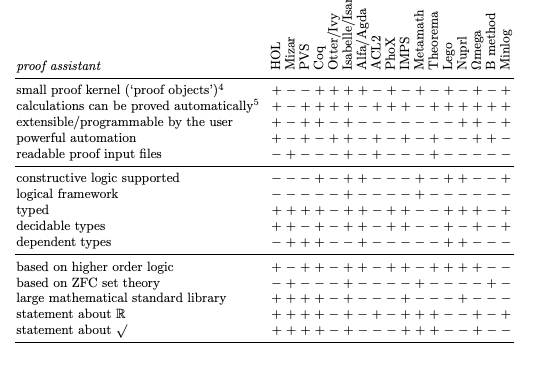

Here’s a comparison (Figure-52) of the 17 provers from Freek’s paper. A “+’ means its present and a “-” that it is not.

In summary, here’s the distribution of theorem provers as per the survey (Figure-53)

Conclusion

Let’s return to the promised takeaways:

- Landscape: We saw a huge dump of 160 efforts out of which we looked at 17 provers with some of their proofs. We further looked at the architectures of a handful of provers noting the emerging complexity of software systems.

- Comparison: We compared the logical systems, the representation and reasoning engines across multiple provers calling out some success criteria and dominating efforts.

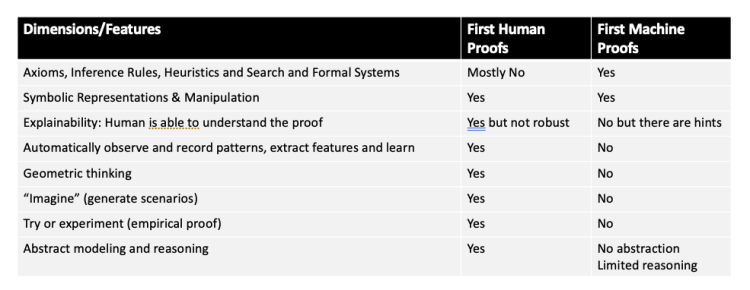

- Status Check: To address this, let us revisit the comparison table (Figure-) from part-1. But a quick digression first:

In the article, “The Work of Proof in the Age of Human–Machine Collaboration“, Stephanie Dick quotes Larry Wos and Steve Winker as having said this in their contribution to a 1983 conference on ATP:

“Proving theorems in mathematics and in logic is too complex a task for total automation, for it requires insight, deep thought, and much knowledge and experience.”

Larry Wos joined Argonne National Laboratory in 1957 and began using computers to prove mathematical theorems in 1963. What is amazing is that he is still working on it! Wos and his colleague at Argonne were the first to win the Automated Theorem Proving Prize in 1982.

With that, lets get back to the original table below (Figure-54):

And our updated table with an extra column to the right below: (Figure-55)

At a high level, it appears that theorem provers have gotten better with logical systems, explainability, geometric reasoning and model checking. There remain issues with graceful failures when decidability and satisfiability cannot be determined. There isn’t much yet on learning and “imagining/generating scenarios”. To borrow from Wos’s and Winker’s statement above, we are still missing the experience (learning), the insight and deep-thought (what I call imagination) bits. And that is precisely what we will dig into in our next and final part. We’ll venture into the role that machine learning, transformers, deep neural networks and commonsense reasoning are beginning to play in the ATP/ITP space. Stay tuned …

Don’t forget to give us your ? !

The story of machine proofs — Part II was originally published in Becoming Human: Artificial Intelligence Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Via https://becominghuman.ai/the-story-of-machine-proofs-part-ii-f97dfa5655ea?source=rss—-5e5bef33608a—4

source https://365datascience.weebly.com/the-best-data-science-blog-2020/the-story-of-machine-proofspart-ii