Linear regression is commonly used to estimate the linear relationship between independent variables* (x₁, x₂, …, x) and dependent…

Continue reading on Becoming Human: Artificial Intelligence Magazine »

365 Data Science is an online educational career website that offers the incredible opportunity to find your way into the data science world no matter your previous knowledge and experience.

Linear regression is commonly used to estimate the linear relationship between independent variables* (x₁, x₂, …, x) and dependent…

Continue reading on Becoming Human: Artificial Intelligence Magazine »

Narrow Artificial Intelligence can seem overwhelming. AI is a complicated thing and is understandably filled with intimidating computational jargon. In this article I’m going to do something foolhardy, and that’s to tell you — the interaction designers — don’t panic. For our jobs, the basics of AI are probably simpler than you think. To make this case, I’m going to…

Of course, as designers, you should be goal-oriented first and foremost. Who are the users? What are their goals? What are their contexts? How do they use the thing? Does it work? That said, you should also be familiar with the material in which you are designing, so you can match the material with the human goal as best as you can. To that end, let me introduce the four categories. These are roughly grouped around major AI technologies.

More on each follows. Note that like any technology, these technologies can be used for good and ill. I’ve tried to provide good examples as much as I could, but sometimes a wicked example is easier to understand. I’ll note when I list those kinds of examples.

A clustering algorithm can look at a bunch of data and identify groups within the data. Use clusterers to save users the work of organizing things into useful groups manually.

Practical examples of clusterers

↑ Inputs: Lots of things

↓ Outputs: Groups within the things

Clustering by itself doesn’t have interactions per se. It’s more of a behind-the-scenes thing. It just tells you what it sees. But its outputs are rarely perfect for human use, and so the basic interactions are related to modifying and curating the results.

Basic interactions with clusterers

1. Subdivide groups

2. Merge groups

3. Modify the definitions of a group

4. Add a group

5. Providing a name and details for a group

6. Delete (or hide) a group

7. (For large numbers of groupings): Filtering and sorting groups

Related concepts and jargon: K-means clustering, unsupervised learning

Clusterers are very tightly intertwined with classifiers since clusterers often create the groups, and classifiers try to put new things into the groups. Oftentimes after providing groups, users will want to look at individual examples to build trust that the clusterer worked, or to move an example from one group to another. But this is an act of classification, which is next.

A classifier can take a thing, compare it to categories it knows about, and say to what category or categories it thinks the thing belongs. (If there’s just one category it’s called a binary classifier, if multiple it’s a multi-classifier.) When said like this, classifiers sound abstract and rudimentary, but they are beneath so many concrete things. Use classifiers to help users identify what a thing is.

Practical examples of classifiers

2. How AI Will Power the Next Wave of Healthcare Innovation?

↑ Inputs: An example thing

↓ Outputs: Categories of the thing, with confidences that the thing belongs in each category

Confidences bear some explanation and attention. Where a person could look at an image and say, “Yeah, that’s an orange tabby cat,” classifiers respond with both the “feature” of the image and its confidence that it got it right. Confidences are most often expressed as a decimal between 0.00 (not confident) and 1.00 (completely confident). So the speculative cat picture might result in something like…

Mammal: 0.99

Domesticated cat: 0.90

Orange: 0.89

Kitten: 0.75

Lion: 0.31

One design task with classifiers is to take those computery-outputs and massage them into something that is more understandable and suited to the domain. Sometimes this is a simple classification, like spam/not spam. Sometimes this can be a prediction with a confidence number out of 5 stars. Sometimes just a prediction with high, medium, and low confidence. Sometimes you can show users a high and a low confidence classification simultaneously to let them be compared. A design task for classifiers is to find the right level of fidelity that helps avoid either false precision or faulty generalization.

It’s also worth noting that in a lot of cases, when the confidence of a classifier is very high, and the classification is correct, interactions can be seamless. The face recognition on your smartphone, for instance, can sometimes go by without your even thinking about it. If an app translates your handwriting perfectly into text, you just move on. The interactions often come when the classification is wrong, or its confidence is lower.

Basic interactions with classifiers

8. Flagging/correcting a false positive/negative: Sometimes a classifier will just get things wrong. Like email putting a party invitation into a spam folder. Users need the ability to at least identify bad classifications. Oftentimes users need more capabilities, like being able to manually assign a new classification and tell the algorithm what to do with similar things in the future. (I wrote in-depth about these use cases in Designing Agentive Technology, where you can read more).

9. Disambiguation: When a classifier’s confidences are below some threshold, it’s best to not just move forward with the unlikely match, but for the system to work with the user to increase its confidence. This back-and-forth interaction is called disambiguation and in some cases repair. If you’ve ever had a chatbot ask you which of several possibilities you actually meant, you’ve experienced disambiguation. If you’ve ever had to repeat something to an interactive voice response system, you’ve experienced repair.

Related concepts and jargon: Supervised learning, Naive Bayes Decision Tree, Random Forest, Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machines, Hidden Markov models

Sidebar: CAPTCHAS are a type of classifier, but they’re upside-down. They’re trying to identify problems that humans can accomplish, but that computers find difficult-to-impossible. They seek to classify you as not-a-computer.

“Regression analysis” sounds like some kind of psychology thing, but it’s a math thing. These algorithms look at the relationship between two or more variables to find correlations, allowing them to predict one variable based on the others. This can include prediction of future events based on models of the past, but it doesn’t have to be about time. Use regressors to infer one variable from a bunch of others, and to sensitize users to (and act on) likely future events.

It’s easier to understand with a toy example. Consider the height and weight of chimpanzees. As they get taller, they tend to weigh more. Because of this correlation, if I give you the height of a particular chimpanzee, you could look on a data table and predict how much it probably weighs. Regressors do this, but for much more complicated sets of variables, with much more complicated relationships to each other.

Note that under the hood, regressors and classifiers are the same task. But the difference from a user perspective is that classifiers output discrete classes, and regressors provide a number within a range (often between 0.0 and 1.0).

Practical examples of regressors

↑ Input: The set of known variables

↓ Output: A number representing the predicted variable (and sometimes the range of error for that predicted variable)

Basic interactions with regressors

10. Updating: Predictions can be updated as new information comes in. Think of estimated time of arrival on a navigation app. How is the user notified? Can they reject the update? What “downstream” recommendations need to change and how?

11. Scenario-izing: Users may want to investigate how different predictions will play out and compare them. In some domains, users may want to document contingency plans for each scenario as a playbook to be used by others later.

12. Refining: After a predicted event happens, users may want to compare actual effects to predictions, in order to improve playbooks.

Related concepts and jargon: regression analysis, supervised learning (this is both related to regressors and classifiers), inference

The newest and arguably most unsettling capability are those that output new things. It’s also the oddball category in this writeup that is not just about one kind of technology. These algorithms use some of the underpinnings of clusterers, classifiers, and regressors (and other things) to help people be creative or creatively solve some problem. (And, it must be said, some malefactors to spread disinformation.) Offer users generators as part of creativity tools. Offer users optimizers to achieve the best and unexpected results in complicated decision spaces, like architecture.

Practical examples of generators and optimizers

↑ Input: Most work from “seed” input like a few lines of text or an image, and all work with massive data.

↓ Output: New images, sounds, or texts

Basic interactions with generators and optimizers

13. Seed/Reseed: The source material, options, and criteria for success, if any.

14. Rerun: If users didn’t like the output.

15. Adjust “drift”: Many generators allow control of how “prim” or “wacky” the results are. A news agency way want prim headlines, but a poet may want the wackiest output they can get their hands on.

16. Explore options: Generative systems can produce a lot of results. As with any large result set, users may need help making sense of them all, or to design parameters that can reduce the number of results. (Or even to design systems that let end-users manage those parameters themselves.)

17. Lock or reweight criteria: If users are happy with some aspects of a generated result, but not others, they should be able to lock those aspects and re-run the rest for new results. For systems that are trying to optimize for certain goals, users may want to change the weightings and see what else results.

18. Save results (of course)

19. Export and extend: When users want to use the selected results as a starting point for doing more manual work, they need the ability to export in a way that lets them continue working.

Related concepts and jargon: neural nets (CNNs, RNNs), generative adversarial networks, deep learning, deep dream, reinforcement learning.

Some basic interactions aren’t tied to any core technology. These aren’t derived from any particular AI capability, but they are important to consider as part of the basic interactions that need to be designed. Many are required by law.

20. Explain that to me: This isn’t always easy. Some AI technologies are so complicated that, even though they’re often right, the way it figured things out is too complicated for a human to follow along. But when decisions can be explained, they should be. And when they can’t, provide easy ways for users to request human intervention.

21. I need human intervention: This is vital because AI will not always reason like a human would. As AI systems are given more weighty responsibilities, users need the option of human recourse. This can often be in the form of objecting to an AI’s output.

22. Override: In systems where users are not beholden to follow an AI’s recommendations, users may need mechanisms letting them reject advice and enact a new course of action.

23. Annotate: Users may need to store their reasons for an override or correction for later review by themselves, their managers, auditors, or regulators. Alternatively, they may want to capture why they chose a particular option amongst several for stakeholders.

24. Let me help correct your recommendation for the future: If a recommendation was rejected or overridden, users may want to tell the AI to adjust its recommendations moving forward.

25. Let me help correct your recommendation for my group: One of the promises of AI is hyper-personalization. Its model may need to adjust to the idiosyncrasies of its user or group of users.

26. Show me what personal information of mine that you have.

27. Let me correct personal information of mine that you have.

28. Delete my personal information from your system.

29. Graceful degradation: If the AI components of a system should fail, users still have goals to accomplish. If the AI is not critical, the system should support the user’s shift into a more manual mode of interaction.

There are distinctions to these use cases when the AI is acting as an agent, an assistant, a friendly adversary, or a teammate. But the domain will determine how those distinctions play out.

We’re fortunate that today many design discussions about AI involve ethical considerations. I don’t want to short-change these issues, but smarter people than me have written about ethics, and summaries risk dangerous oversimplification. For now, it is enough to remind you that understanding what AI can do is only part of understanding what it should and should not do.

This article is just about the likely interactions that can have good or bad effects depending on how they’re implemented. It is you and your team’s responsibility to work through the ethical implications of the things you design and to design with integrity — or to raise the alarms when something shouldn’t be designed at all. At the end of this article, you’ll find a list of links to better sources if you want to know more.

The field of AI is changing all the time. New capabilities will come, but for now, these 29 are the use cases you are likely to run into when designing for narrow AI. But these also aren’t the end of it. These must be woven together and expanded upon given your particular domain and application. I expect most sophisticated products will use more than one category simultaneously. For example, the supply chain software that I work with at IBM, Sterling Supply Chain Software business assistant, built on Watson Assistant, uses all of these…

Clusterers: To analyze inputs for a given bot and identify common topics and questions that went unanswered. These become candidates for future development.

Classifiers: To understand the user’s intents from their natural language inputs, as well as the “entities” (things) that have been mentioned.

Regressors: To suggest playbooks based on ongoing conversations.

Generators: For generating natural language responses.

And you look back over the lists of basic interactions, I hope you realize that these are use cases you can handle. Disambiguation, optimizer criteria, and scenario-izing may be the most novel interactions of the bunch. But things like managing groups, flagging bad results, and exploring multiple options are something you could design outside of AI.

These four capabilities are like building blocks. They need to be embedded in larger systems that support the humans using them, the environment in which they operate, and more to the point — supporting the user’s goals for using them in the first place. That’s why user-centered design is still key to its successful implementation. You got this.

Special thanks to the contributors to this article:

A Primer of 29 Interactions for AI was originally published in Becoming Human: Artificial Intelligence Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Via https://becominghuman.ai/a-primer-of-29-interactions-for-ai-866164ab12f0?source=rss—-5e5bef33608a—4

source https://365datascience.weebly.com/the-best-data-science-blog-2020/a-primer-of-29-interactions-for-ai

Originally from KDnuggets https://ift.tt/31XtyEU

Originally from KDnuggets https://ift.tt/2OFe6KI

Originally from KDnuggets https://ift.tt/31Uv6zs

Originally from KDnuggets https://ift.tt/3mDaHbS

Computer Vision is a field of study that focuses on creating digital systems that computers can process, analyze and gain high-level understanding from digital images or videos by converting them into arrays of matrixes. In this advanced age of technology, computer vision has made self-driving cars, fatal illness detection, and facial recognition possible. In this blog, I wanted to show all the basics of computer vision by demonstrating OpenCV key features.

OpenCV (Open Source Computer Vision)

In order to download OpenCV, we need to download the module by using

pip install opencv-python

Load and Display an image

OpenCV makes it really easy to load images using the function, cv2.imread(‘file path’, ‘color’). In this function, we can adjust the color in either grayscale or RGB scale. We can customize the ‘color’ of the image by using cv2.IMREAD_COLOR or -1 for color images and cv2.IMREAD_GRAYSCALE or 0 for black/white images. In order to display the image, use cv2.imshow(‘name’, ‘image’) , and it will open a new window that displays the image. The code cv2.waitkey(0) will close the new window with any key and follow by cv2.destroyAllWindows() to destroy all windows (git bash).

import cv2

img = cv2.imread('img_folder/hello.png', 0)

cv2.imshow('image',img)

cv2.waitkey(0)

cv2.destroyAllWindows()

Flipping, Resizing, and Saving the Image

This functioncv2.resize(‘image’, (size, size)) changes the size of the image by manually inputting the height and weight. Another way to change the size is by shrinking or expanding the size of the image by using cv2.resize(‘image’, (0,0), fx = 0.5, fy =0.5). This will shrink the size of the image by half and you can input different fx and fy to expand or shrink the image. When the image comes inverted and you want to mirror it, you can use the flip method to make it your liking. The code cv2.flip(“image”, -1): -1 will mirror it and 0 will flip it vertically. In order to save the image, you use cv2.imwrite(‘image’, img), this will save your edited image to the current directory.

img = cv2.resize(img, (256,256))

img = cv2.resize(img, (0,0) fx = 2, fy = 2)

img = cv2.flip(img, -1)

cv2.imwrite('new_image.jpg', img)

Accessing your Webcam

With OpenCV, they made it easy to access your webcam and capture images. The function cv2.VideoCapure(0) will access your primary webcam and enter a different number to access different video-recording devices. The function, the frame is the image, and ret tells you if the webcam is functional. When accessing your webcam, you assign keys on your keyboard to perform different actions in the program. For example in the code below, it will take a screenshot when you press the space key and end the program if you press the ESC key. In order to access the keys, we use the function key = cv2.waitKey(1) and we are able to access the different keys on the keyboard by taking the module of that function, then it will give us the ASCII key. You can set the statement as if key%256 == 27: this means that by pressing the ESC key, this if statement will activate.

import numpy as np

import cv2

cap = cv2.VideoCapture(0)

while True:

ret, frame = cap.read()

cv2.imshow('frame', frame)

key = cv2.waitKey(1)

if key%256 == 27:

print('Esc key hit, closing webcam')

break

elif key%256 == 32: ## space key

cv2.imwrite('mywebcam.jpg', img)

## it will take an screen shoot when space bar is hit cap.release() ## it releases the VideoCapture

cv2.destoryAllWindows() ## ends the function

2. How AI Will Power the Next Wave of Healthcare Innovation?

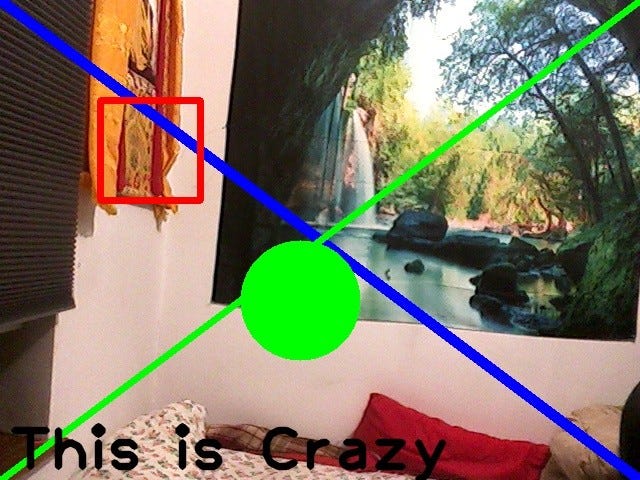

Drawing Lines, Circles, and Text

When accessing your webcam, image, or video, you might want to display text, lines, or circles in certain positions. When detecting faces, objects, or anything else, you need to have a frame around the subject, for in order labels or identify that you will need to draw or write on or around it. First, you need to figure out the height and width of the frame. cam.get(3) will give the width and cam.get(4)will give you the height of the frame(image). The function cv2.line(‘img’, (0,0), (width,height), (255,0,0),10) will draw a line from the left top corner to the bottom right corner. The function needs the image, starting position (0,0), ending position (width, height), color (255,0,0), and line thickness (10). The rectangle function has the same syntax except for cv2.rectangle(). In order to draw a circle, you need to use cv2.cirlce(img, (300,300), 60, (0,255,0),5). The function needs the image, center position (300,300), radius (60), color (0,255,0), and line thickness (5). In order to write text on the webcam, you need to use cv2.putText(img, ‘This is Crazy’, (10,height -10), font, 4, (0,0,0),5, cv2.LINE_AA). This function needs an image, text (‘This is crazy’), center position (10, height -10), font, the scale of the font (4), color (0,0,0), line thickness (5), linetype (cv2.LINE_AA). The “linetype” will make the text look better and it is highly recommended by the documentation of OpenCV.

import cv2

cam = cv2.VideoCapture(0)

if not cam.isOpened():

raise IOError("Cannot open webcam")

while True:

ret, frame = cam.read()

width = int(cam.get(3))

height = int(cam.get(4))

img = cv2.flip(frame, 1)

img = cv2.line(img, (0,0),

(width, height), (255,0,0), 10)

img = cv2.line(img, (0, height),

(width, 0), (0,255,0), 5)

img = cv2.rectangle(img, (100,100),

(200,200), (0,0,255), 5)

img = cv2.circle(img, (300,300),

60, (0,255,0), -1) ##-1 fills the circle

font = cv2.FONT_HERSHEY_PLAIN

img = cv2.putText(img, 'This is Crazy',

(10,height-10), font, 4,

(0,0,0), 5, cv2.LINE_AA)

cv2.imshow('webcam', img)

k = cv2.waitKey(1)

if k%256 == 27:

print("Esc key hit, closing the app")

break

elif k%256 == 32:

cv2.imwrite('img.jpg', img)

print("picture taken")

cam.release()

cam.destroyAllWindows

The image below is the result of the code above.

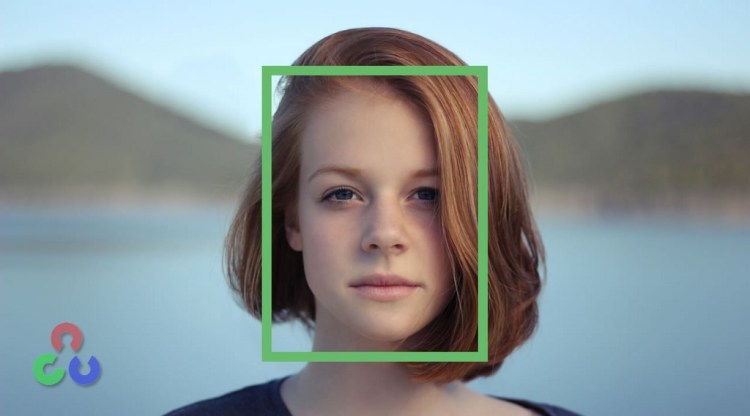

Detecting Faces using Haar Cascade

The next step would be detecting faces in a frame or image. OpenCV has a built-in machine learning object detection program that will identify objects called Haar Cascade classifiers. For detecting faces, it has trained from a large number of color images of faces and negative(black-white) images of non-faces to train it. Below is a link to the XML file of face-detection Haar Cascade that you will need to have in order to detect faces.

The function cv2.CascadeClassifier(cv2.data.haarcascade + ‘filepath’) reads in the XML file for face detection from a file path. After that, you do the steps taught above to open the webcam and then you use face_cascade.detectMultiScale(img, 1.3,5) , which needs an image, min size (1.3), and max size (5). Then, it will find the face and then you use the rectangle function to draw around the face.

import cv2

import numpy as np

face_cascade = cv2.CascadeClassifier(cv2.data.haarcascades + 'haarcascade_frontalface_default.xml')

cam = cv2.VideoCapture(0)

while True:

ret, frame = cam.read()

img = cv2.flip(frame, 1)

face = face_cascade.detectMultiScale(img,1.3, 5)

for (x, y, w, h) in face:

cv2.rectangle(img, (x,y), (x+w,y+h), (0,128,0),2)

cv2.imshow('image', img)

k = cv2.waitKey(1)

if k%256 == 27:

break

cam.release()

cv2.DestroyAllWindows()

After running the program, it will detect the face and draw a rectangle around the face like the picture below.

In this blog, we learned how to load, save and display an image. Also, we are able to manipulate the image by using flipping and resizing. We can also access the webcam and use the keys to add features like screenshots and we are able to draw lines, circles, and text on the webcam as well. After combining all the skills that we learned, we are able to detect faces using the haar XML file.

Tenzin Wangdu – Data Science Fellow – General Assembly | LinkedIn

Computer Vision using OpenCV in Python was originally published in Becoming Human: Artificial Intelligence Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Hello everyone, This is my very first post here. My name is Farhad and I am a data scientist and entrepreneur. Right after my graduated…

Continue reading on Becoming Human: Artificial Intelligence Magazine »

Machine learning and AI courses and recourses for start-ups

Continue reading on Becoming Human: Artificial Intelligence Magazine »

Originally from KDnuggets https://ift.tt/3dORhwD